I don’t consider myself a Buddhist. But I often find myself digging stories about Siddhartha Gautama, the ancient spiritual master known as the Buddha.

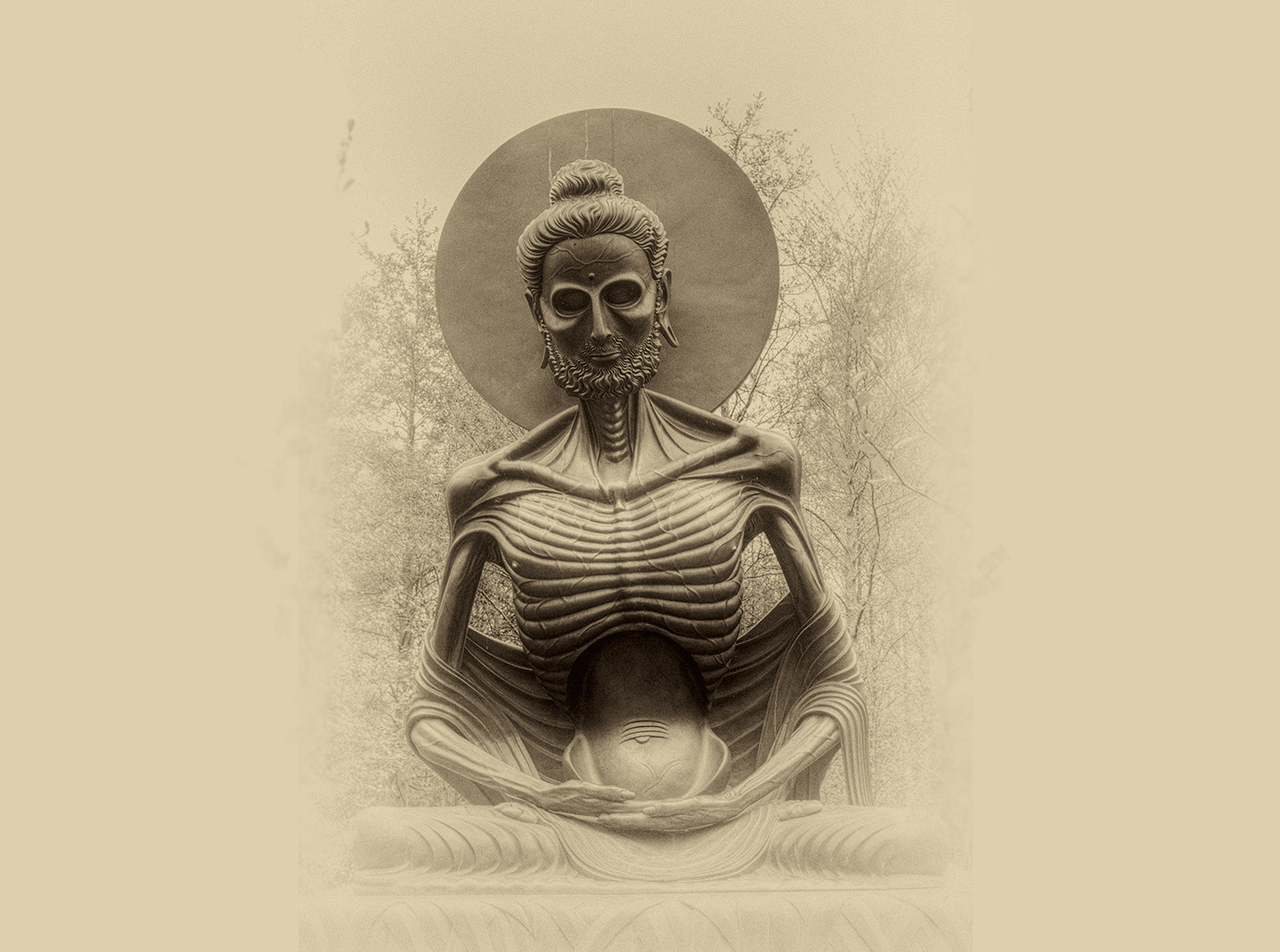

One lesser-known story is when Siddhartha almost died from starvation. He’d been wandering the jungle practicing intense forms of meditation and austere living. He tortured his body to try to overcome its desires and needs, eventually limiting his daily diet to a few grains of rice.

“When I touched my belly, I would feel my backbone, and when I went to urinate, I would fall over,” he would later say.

Collapsed near a river at the edge of death, he realized that starving himself was only causing more suffering.

With the help of a peasant woman who nursed him back to full strength, he soon started a spiritual community and developed the practices and teachings that would become known as Buddhism.

I like this story for three reasons.

One, it reminds me that there’s a limit to the hustle.

Capitalism tells us otherwise. Relaxation is shamed in our society. Unless you’re rich, which means you deserve that vacation on your yacht. Otherwise, work harder, start a side hustle, be more productive, wake up earlier, do these ten things in your daily routine, blame poor people if you’re still unsatisfied with your life.

I’ve internalized these messages like a sponge. If I’m not careful, I’ll forget to take breaks, work on the weekends, start new projects before I’ve finished others. Eventually, I’ll burn out and collapse in my bed.

Once, in my mid 20s, I ended up in the hospital after half my body went numb. I probably wasn’t at the edge of death. But I got the message that if I continued working hard and partying harder, I might get there.

Two, it reminds me that I can’t do it alone. It being, live the life I so desperately want to live. A life lived fully.

Part of the reason Siddhartha almost died is because he was alone. He was fortunate a peasant just so happened to be walking by when he collapsed.

Eventually, his cousin Ananda would say to him, “Lord, I’ve been thinking. Spiritual friendship is at least half of the spiritual life.”

Siddhartha replied, “Ananda, that’s wrong. Such a view is not correct. Spiritual friendship is the whole of the spiritual life!”

As the Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr once wrote, “Nothing we do, however virtuous, can be accomplished alone; therefore we must be saved by love.”

Capitalism, on the other hand, says lift yourself up by your own bootstraps. Do it yourself. Maybe start a family and buy a house in the suburbs. But when it comes down to it, you’re on your own. Have some personal responsibility!

Whiteness, which infects all of us, says so too. Being “white” has robbed me of my ancestors’ traditions, rituals, and ways of relating. It’s tricked me into thinking that I came from nowhere. That I didn’t come from English settler-colonialists who stole this land and German indentured servants who were all but forced to come here. That I’m not part of a community. That I’m self-made.

The third thing I like about the story is that it highlights the danger of toxic masculinity.

During his hustling phase, Siddhartha had no time for nourishing food, women, or anything considered soft. “All of these were temptations and a potential cause for [his] downfall,” writes the Buddhist nun Thanissara.

But “through the humble presence of a loving and caring woman,” Thanissara writes, “he saw the beauty of the river, of the sun shimmering on the tress and grasses, and of the graciousness of life in its abundance. The problem was not the world; the problem was his aversion to it.”

The peasant woman represents feeling emotions rather than stuffing them down. Embracing rather than rejecting and even hating anything that appears feminine. Collaborating with, rather than dominating over.

She also represents the belittlement of so-called “woman’s work.”

As socialist feminist Nancy Fraser says, with the rise of capitalism, “[The creation and maintenance of social bonds] was left behind, relegated to a new private domestic sphere, where it was sentimentalized and naturalized, performed for the sake of ‘love’ and ‘virtue,’ as opposed to money.”

We should always remember that the peasant woman is a crucial figure in Siddhartha’s awakening and the formation of Buddhism, a world religion now with over 535 million followers.

All of this is to say: Rest is a worthy thing to do, community matters, and patriarchy must go.

I’m a writer, meditation teacher, and host of the Meditation for the 99% podcast. My weekly email newsletter helps you bring mindfulness to work, relationships, and politics. Subscribe here.