This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they are a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice.

Meet them at the door laughing and invite them in.

Be grateful for whatever comes.

Because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

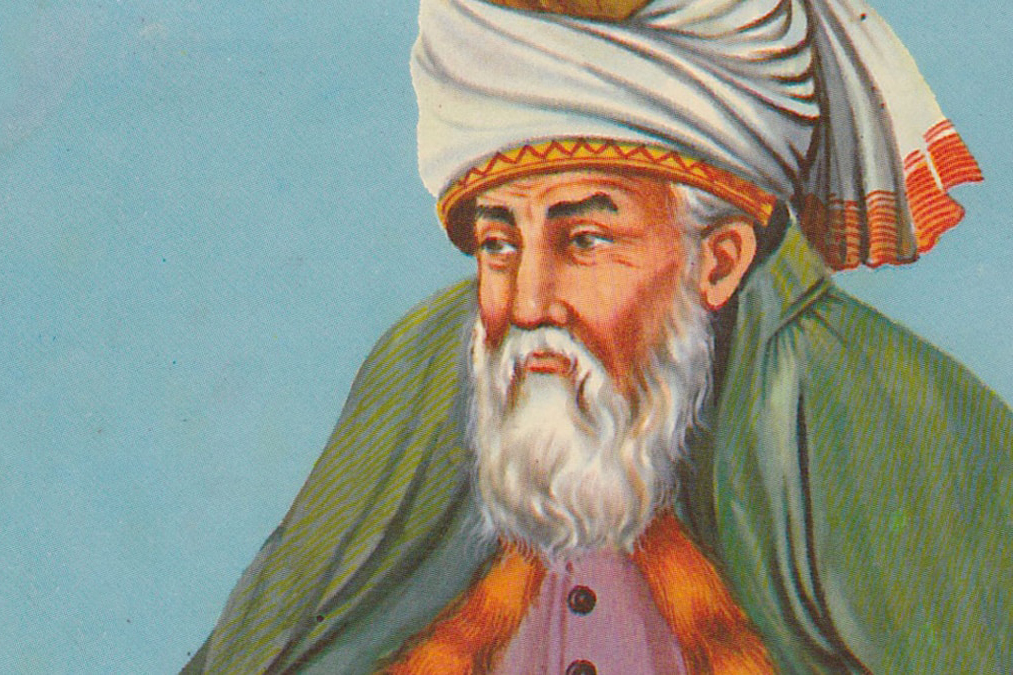

I’ve heard the 13th century poet and Sufi mystic Rumi’s poem “The Guest House” more times than I can count. It’s a staple in U.S. spiritual communities, from psychotherapist and meditation teacher Tara Brach to NPR’s On Being.

But during the COVID-19 crisis, the poem’s metaphor is more metaphoric than ever—which gives it a fresh resonance. For the foreseeable future, we can’t have anyone over without risking our health. No guests will be visiting our houses.

Obviously, Rumi’s guest house is inside of us, and what he meant by a “new arrival”—an “unexpected visitor”—was an emotional state, a mood.

Like me, you’re probably feeling all kind of moods right now.

Part of me wants to drive to some fictional place where coronavirus doesn’t exist.

Part of me is scared that I or a friend or my family will get sick.

Part of me is angry at big corporations and Wall Street for using the government to bail out themselves rather than poor and working people.

Part of me is whiny like a 16-year-old about being cooped up for the rest of this crisis.

I’m using the word “part” intentionally. (The concept of parts, or sub-personalities, comes from the work of psychotherapist Richard Schwartz. I learned it from my therapist.)

As Rumi says, there’s immense value in trying to welcome all of our parts—to treat each guest honorably. Keyword: trying.

No one wants to feel negative emotions—they’re painful. Emotions like fear and anger not only burn a hole in your chest or paralyze your shoulders but they also mean (in the eyes of your inner critic) that you’re weak or not a nice person.

Rather than feel the pain, we judge ourselves for experiencing the emotion. We try to talk ourselves out of it, rationalizing why we shouldn’t feel the way we do. We ignore how we feel and focus on making others happy. We numb with alcohol and other escapes.

Sometimes, the emotion is so strong that we can’t help but act out. We get swept away by fear and catastrophize, imagining the worst possible outcome (the whole world is going to end!). We get caught up in anger and try to pick a fight. It goes without saying that this often leads to even more pain and suffering.

Whether we ignore or get lost in negative emotions, we’re trying to avoid the pain, which is reasonable. Who wants to feel all the feelings right now? There’s too much. A little distraction is OK.

But, as Rumi writes, there’s power in welcoming our emotions, moods, and mind states—our parts. Because what the parts are doing is trying to protect us.

That restless part of me that wants to run away is trying to protect me from feeling the slow burn of boredom.

That part that’s afraid is trying to protect me from facing the unprecedented uncertainty of the crisis.

That part that’s angry is trying to protect me from the undeniable truth that our society is cruel and unfair.

Our parts are like little kids. They want to do the right thing, but they’re extreme in their thinking. Either run away for good or stay here and die. Either start a revolution or get crushed by the gears of capitalism.

Would you kick a toddler out of the house if they were anxious, angry, or afraid? Of course not. You’d treat them like a child. You’d try to understand why they’re acting the way they are. You’d soothe them until they calmed down.

One of my loudest parts right now—and pretty much all the time—I like to call “striver.” It shows up as anxiety about getting things done, overplanning, preparing for the future. Right now, it wants me to buy up every bag of frozen vegetables and roll of toilet paper, which is unnecessary and foolish.

But it’s just trying to protect me. It thinks that if I don’t get enough done then others will perceive me as a failure, which will be painful.

Once I started seeing my inner striver as a young child just trying to help, I’ve been less caught up in trying to prove that I’m on top of everything all of the time. I can still get things done like the most Type A person alive. But I can also relax — like, fully relax, for the first time in my life.

The more compassion you muster for yourself amidst negative emotions the less likely you’ll ignore or get lost in them, and the more likely you’ll be able to respond rather than react in the days ahead. The more you notice and welcome your parts, the less likely they’ll take over.

As meditation teacher Jack Kornfield writes, “[We can take] unwanted sufferings, the sorrows of life, the struggles within us and the world outside, and [use] them as a ground for nourishment of our patience and compassion, the place to develop greater freedom.”

As Rumi’s poem says, “Be grateful for whatever comes. Because each has been sent as a guide from beyond.”

Want to start meditating or meditate more often?

My ebook, How to Get Out of Your Head, will help you start or stick with a regular meditation practice. Get it for free here.

Listen to my podcast

On Meditation for the 99%, I take meditation out of faraway monasteries, expensive retreat centers, and Corporate America, and bring it to work, relationships, and, especially, politics. Listen everywhere podcasts are available.