One of my earliest memories is sitting cross-legged in front of the TV and getting some news that rocked my little kid world.

My mom was talking on the cordless phone behind me in the kitchen. A lawnmower blared outside.

I felt free, content, and safe. My family’s quiet, suburban Maryland home oozed 1990s middle-class prosperity. Five types of cereal sat in the pantry. Fifty cable channels awaited my eyes.

My mom came over to talk to me. “They wanted to hold you back from first grade. But I told them no,” she said. “You can handle it.”

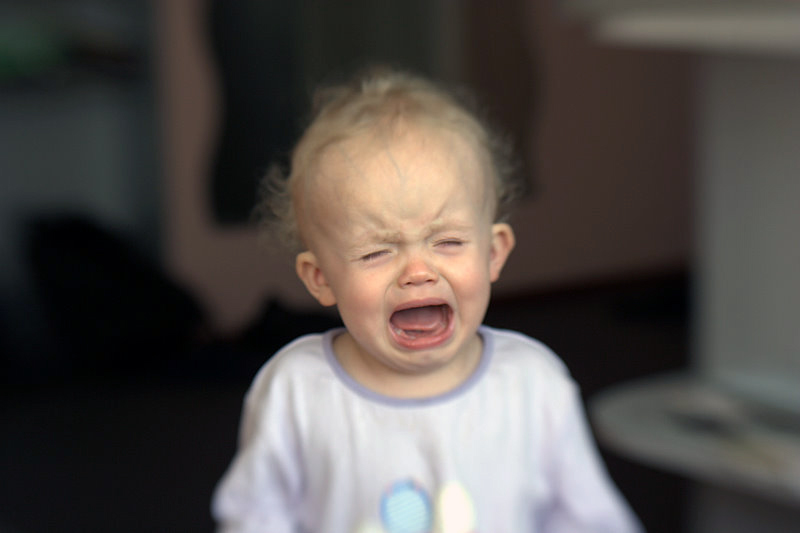

An alarm rang inside my body. My throat and shoulders tensed. What did I do wrong? Why did they want to hold me back? Is Mom mad at me?

This is an example of what psychologists call developmental trauma, or small “t” trauma.

It definitely wasn’t abuse. It wasn’t even mean. If anything, my mom was defending me. She believed in me, which should’ve felt empowering.

But my little developing brain didn’t take it in that way. I got the opposite message: that I wasn’t enough.

I’d been the class clown. Learning that my teacher had been evaluating me from afar — which was her job, of course — filled me with shame. From then on, I was going to at least appear as though I was on task and working hard. I didn’t want to feel that pain ever again.

“You can have childhoods were no overt trauma occurs,” says the physician and addiction expert Gabor Maté. “But when the parents are just too distracted, too stressed to provide the necessary responsiveness, that can also traumatize the child.”

I don’t say all of this to blame my mom. She was doing the best she could. She was in her early 30s — younger than I am now — with my baby sister on her hip. She was kicking ass in a male-dominated industry, information technology. And she wanted the best for me.

Developmental trauma just happens. No one can avoid it. Because no parent can be completely attuned to their kid’s emotional needs 24/7. Modern life with its smaller families and endless demands is, in a word, demanding.

I say all of this to say that trauma — both big “T” and little “t” — is what makes us who we are.

It wasn’t until I started seeing a therapist that I saw the connection between my kindergartner and adult selves.

I often feel like I’m behind and need to catch up. Behind who or what? I don’t know. This story — that I need to hustle or something bad might happen — appears first thing in the morning. It tells me to get to work on something, anything, right now.

No wonder I work on weekends when I don’t have to, start new projects before I’ve finished others, and forget to take breaks. No wonder I’m addicted to the hustle. A part of me is still trying to prove to my kindergarten teacher that I’m good enough.

My point is: Working with trauma is key to personal growth.

We can do all the things. The meditation, the trendy diets and workouts, the self-help books. But unless we get a sense of our trauma, we’re likely just acting out old patterns that don’t necessarily serve us. Patterns that keep us hurting people we love, doing work we don’t want to do, not living fully.

It’s also a useful way to look at changing society too. What are white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism if not collective traumas? They cause harm to all of us.

Even white, heterosexual men like me. I don’t have #MedicareForAll, a four-day workweek, and two months of vacation because racism keeps the working class from coming together to win those things. The planet is burning, flooding, and drying up because of climate change. I’ve had to scratch and claw to learn how to feel my emotions, because I was socialized as a man.

In other words, trauma causes disconnection. Which then causes harm.

And if we’re not careful, we can live a whole life disconnected from who we really are. Like the man in Bruce Holland Rogers’s story “Dinosaur”:

When he was very young, he waved his arms, snapped his massive jaws, and tromped around the house so that the dishes trembled in the china cabinet

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake,’ his mother said. ‘You are not a dinosaur! You are a human being!’

Since he was not a dinosaur, he thought for a time that he might be a pirate. ‘Seriously,’ his father said to him after school one day, ‘what do you want to be?’ A fireman, maybe. Or a policeman. Or a soldier. Some kind of hero.

But in high school they gave him tests and told him he was good with numbers. Perhaps he’d like to be a math teacher? That was respectable. Or a tax accountant? He could make a lot of money doing that. It seemed a good idea to make money, what with falling in love and thinking about raising a family.

So, he became a tax accountant, even though he sometimes regretted it, because it made him feel, well, small. And he felt even smaller when he was no longer a tax accountant, but a retired tax accountant. Still worse: a retired tax accountant who forgot things. He forgot to take the garbage to the curb, to take his pill, to turn his hearing aid on. Every day it seemed he forgot more things, important things, like where his children lived and which of them were married or divorced.

Then one day, when he was out for a walk by the lake, he forgot what his mother had told him. He forgot that he was not a dinosaur. He stood blinking his dinosaur eyes in the bright sunlight, feeling its familiar warmth on his dinosaur skin, watching dragonflies flitting among the horsetails at the water’s edge.

I’m a writer, meditation teacher, and host of the Meditation for the 99% podcast. My weekly email newsletter helps you bring mindfulness to work, relationships, and politics. Subscribe here.

Download my free ebook on how meditation can transform your life.

Photo by Olga.